by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

The idea has been advanced, in certain circles, that A. C. Swinburne was a member of the so-called Spasmodic School or was, in some respects, a proponent of its principles and practices.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Though Swinburne was susceptible to influence from a number of quarters – he was a marvelous imitator who has been called the most gifted mimic in English letters for his uncanny ability to parody the style of other writers – most of his inspiration sprang from two distinctive and very different sources – classical literary models and contemporary visual aesthetics. From the Pre-Raphaelites and related contemporary visual artists who were his confederates, from his close friend James Abbott McNeill Whistler and, most particularly, from another great proto-impressionist – J. M. W. Turner – who was a friend of his grandfather, and a set of six of whose watercolors was so treasured a family possession that Algernon’s mother carried it with her in a special traveling case wherever she went – Swinburne drew much of his formation.

With regard to the Spasmodists, however, Swinburne stood so far above and apart both in originality and in grandeur, as to be likened to an eagle atop Olympus gazing down upon pismires crawling on a stinkweed in meadows leagues below. Swinburne went his own way and had no association with the Spasmodists, either formally or otherwise. From no plausible perspective whatsoever does he share characteristics with those construed "spasmodic."

Spasmodic loosely designated "neoromantic yearners toward the cosmic, exploiters of intensity and formlessness," whose "main feature was said to be an undercurrent of discontent with the mystery of existence, characterized by vain efforts, unrewarded struggle, skeptical unrest, and an uneasy straining after the unattainable." Elsewhere, it is defined as "a willful delight in remote and involved thinking, abrupt and jerking mental movements, and 'pernickitieness' of expression."

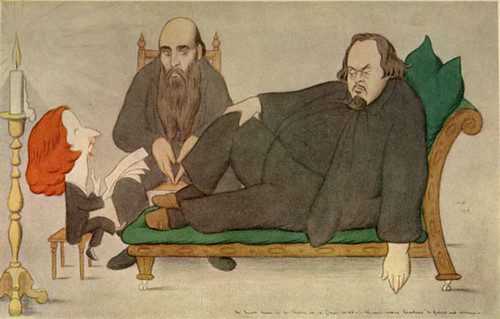

Caricature by Max Beerbohm

The Small Hours in the Sixties at 16, Cheyne Walk, Algernon Reading Anactoria to Gabriel and William

From the vantage of half a century after the evaporation of the Spasmodic movement, Lafcadio Hearn devoted a lecture to the subject. He had this to say:

The sarcastic term "spasmodic" must not be taken literally. It was unjust and the school, although having no great sustained force, did some good work and must not be despised. Some of the best examples have found their way into the best Victorian anthologies, proof positive that the school has merit. If it could not live, that was because its keynote was strong emotion, and you cannot keep up such a tone indefinitely. The school exhausted itself at an early day.

The term Spasmodic refers to the faults of the school. The meaning of the word "spasmodic" is, as I told you, excess of emotion wrought up to the point of morbidness or sickness. But this does not mean that emotion is to be condemned because it is too strong. On the contrary such emotionalism, in real life, indicates weakness, sickness, disease of the nerves, loss of will power. An emotion cannot be too strong for artistic use. But such passions, when artistically expressed, come like sudden storms and as quickly pass; for they are the passions of powerful and healthy men and women. Not so in the case of sickly or mawkish feeling; that is long-drawn and wearisome like the crying of a fretful child, or like the complaining of a sick man whose nerves are out of order. In the case of a child crying for good reason, we are sorry, and try to comfort the child; if the crying goes on too long, if the child continues to cry long after the pain is over, we become tired, and think it ugly as it cries. And if the child persists in crying for another hour, we suspect a malicious intention, and we become angry with the child. Now the Spasmodic poets make us angry in the same way; they cry without reason. Fledgling poets are likely to be too pathetic. Emotion must be compressed like air to serve an artistic object. Emotion in literature is, in the same way, a motive force; but you must compress it to get power. This the poets of the Spasmodic School refuse to do.

Nevertheless, they obtained immediate, though brief, popularity – which encouraged them to cry still louder than before. But why? Simply because to persons of uncultured taste the higher zones of emotion are out of reach. Their nerves are somewhat dull; they are moved by very simple things, and would not be moved at all perhaps by great things. Everywhere there is a public of this kind, to whom lachrymose emotion and mawkish sentiment give the same kind of pleasure that black, red and blazing yellow give to the eyes of children and savages. When the English public learned the faults of what they were admiring, they dropped the Spasmodics and forgot their beauties as well as their faults.

There was a belief prevalent in certain circles at the time that Tennyson and his followers were too cold and that a more emotional school of poetry was needed. The Pre-Raphaelites had the same opinion. But while the Pre-Raphaelites went in the right direction to improve on the methods of the earlier Romantics, the Spasmodics went to work in the wrong direction. They exaggerated pathos without perceiving that the more room given to it, the weaker it becomes. Nevertheless, before they failed, they succeeded in giving a few beautiful things to the English anthologies, and several of these are by Dobell. He generally takes a death bed scene or a tragedy of some kind, and heaps up the sorrow at wearisome length. Arthur O’Shaughnessy but partly belongs to the group. He is not always a Spasmodic, but always a Rhapsodist. He was a clerk in the British Museum. Like all members of this school, he was nervous, sensitive, sickly and, to a great extent, unhappy. He sang of his own pains, mostly, and sang best when he was most unhappy. Besides poetry of regret, he wrote The Silences and The Fountain of Tears, this last a typical poem of the school: it pushes the emotion to the extreme of rhapsody. In the poem there is a spring in some retired place made of the tears of all mankind. In the poem the spring of tears at first appears to well up very gently and softly, with a music in its flowing that brings a strange kind of consolation to the hearer. But gradually the stream becomes strong, the ripples change to waves, the waves to billowings, and at last the flowing threatens to drown the world. So the imagination is carried almost to the edge of the grotesque.

It must be remembered that the Spasmodic poets, fighting for the expression of sincere emotion in literature, were themselves nearly all weak, sick, unhappy persons; and many of their mistakes must have been due to nervous conditions. All the more do they deserve credit for having been able to add something to the treasure-house of English poetry, especially something of a new kind. It must not be forgotten, at the same time, that their principal weakness constitutes a literary object lesson. To dwell upon an emotion at an unnecessary length is always dangerous and not necessarily likely to be powerful.

The Spasmodists were made a laughingstock by Aytoun’s burlesque Firmilian: A Spasmodic Tragedy which poked fun at the spasmodic fashion for whiny dramatic monologues in verse frequently structured so that the speaker was a maundering, self-indulgent, woe-is-me-spouting poet.

Thus we see that, though the term "spasmodic" was meant to deride and ridicule, the school has a legitimate claim to a place in history, despite its limited credo. But any affiliation of spasmodism with Swinburne or the ascription to him of its traits remains a shallow and grossly inaccurate assessment.

***

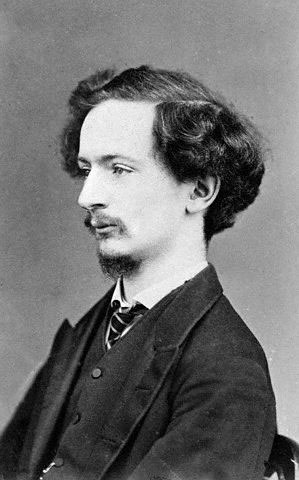

Lord Redesdale on Swinburne (childhood)

What a fragile little creature he seemed as he stood there between his father and mother, with his wondering eyes fixed upon me! Under his arm he hugged Bowdler's Shakespeare, a very precious treasure, bound in brown leather, with, for a marker, a narrow slip of ribbon, blue I think, with a button of that most heathenish marqueterie called Tunbridge ware dangling from the end of it. He was strangely tiny. His limbs were small and delicate; and his sloping shoulders looked far too weak to carry his great head, the size of which was exaggerated by the tousled mass of red hair standing almost at right angles to it. Hero-worshippers talk of his hair as having been a 'golden aureole.' At that time there was nothing golden about it. Red, violent, aggressive red it was, unmistakeable, unpoetical carrots.

His features were small and beautiful, chiselled as daintily as those of some Greek sculptor's masterpiece. His skin was very white — not unhealthy but a transparent tinted white, such as one sees in the petals of some roses. His face was the very replica of that of his dear mother, and she was one of the most refined and lovely of women. Another characteristic which Algernon inherited from his mother was the voice. All who knew him must remember that exquisitely soft voice with a rather sing-song intonation. His language, even at that age, was beautiful, fanciful and richly varied. Altogether my recollection of him in those school days is that of a fascinating, most loveable little fellow.

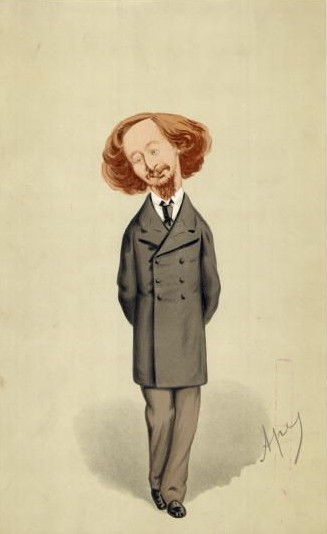

Ecce Barditus

In the poet's maturity, a close friend remarked, "Even when I knew Swinburne only by fleeting glimpses, his personality struck me as something quite out of the ordinary. To begin with, he looked what we call "a celebrity." Having once seen him, much less met him, no one could fail to understand he had come into contact with a very extraordinary being, for certain characteristics removed Swinburne definitely outside the pale of ordinary mortals. Had I met him for the first time in the street or in a room, and not knowing he was Swinburne, had been asked to guess what manner of man he was by profession, I should unhesitatingly at the first glance have said " Poet."

Often when he sat opposite me at meals I would mentally frame Swinburne's head in the pianist's wealth of copper-coloured hair and the resemblance between them would then become positively surprising. But his hair had never been copper-coloured. When his cousin first showed me a lock of Algernon's hair, I could hardly believe such a colour could have grown on a human head. It was not a bit like the hair so often described as "the sort Titian would have loved to paint"; it was just a fiery red.

His eyes were what specially attracted me. They were wonderful, and by far the best feature of his face. If the eye is the window of the soul, truly the eyes of Swinburne spoke for him. I would look at him long and searchingly across the table to try to ascertain what colour they really were. Sometimes they would look soft and tender enough to suggest pansies, at other moments they seemed to be greyish green; and, again, I would think the speckles in them made them marvellously expressive. I have seen them dance and catch fire, according to his various moods. When he read aloud any passage requiring dramatic emphasis, these speckles would grow more radiant and quiver with every cadence of his rather high-pitched voice.

Taking it for granted that Swinburne possessed a superabundance of hair as a young man, I cannot agree with those who think that he possessed a head too big for his body. I would have been the first to have noticed any abnormality of this sort, had it existed. In figure he was slender and boyish, the top-heavy look with which he is credited was no doubt due to the thick hair standing out bush-like from both sides of his head.

Had Nature given Swinburne a body worthy of his mental gifts, he would have been better looking than the Apollo Belvedere. But it was other-wise decreed. His facial features were remarkably good, but his figure was against him. He would have been handsome if he had been a few inches taller and his figure good. But he was short, and his shoulders were far too sloping. His physical imperfections had become less noticeable when I knew him, for he had 'filled out' since the days of "Dolores" and "Chastelard," and his lim

bs, unusually muscular, for a man of his size, had taken on a more solid look. His hands were not beautiful or well-shaped, and they were not particularly small. I would often look at his rather podgy digits and prosaic finger nails. [Ed. - I love this woman.]

In the days of his young manhood, Swinburne may or may not have evinced a partiality for fine clothes, but I am sure his good sense never allowed him to adopt any sort of eccentricity of attire. The poet of tradition and the stage has always something of the guy about his clothing. He wears a pair of rusty black trousers, baggy at the knees, a nondescript waistcoat, and a shabby velveteen coat surmounted by a very low turned-down collar with a huge bow under it. His hair is long, and his hat is an umbrageous sombrero.

Swinburne's attire, as I observed it, flatly contradicted this caricature. He took great pains to avoid advertising his metier. He did not wear his hair long; it only reached the nape of his neck, and the little he possessed was often cut by the barber.

He was always very plainly dressed, and I never saw him wearing any other sort of tie than a plain black silk one. At home, and sitting restfully in his chair with a book, he offered no mark for the caricaturist. But outside, when he had donned his wideawake, he somehow looked eccentric. For one thing he braced his trousers too high; in his absence of mind, he would pull them above the ankles, showing several inches of white sock. Furthermore, he had a curious prancing gait, and his deliberate way of flinging out his feet before him as he trod the ground reminded one of a dancing-master or a soldier doing the goose-step.

With his head thrown stiffly back and his body almost rigid from the waist upwards, Swinburne out-of-doors seemed to me an individual distinct from the Swinburne at home.

***

Permanent links to this four-part column

Part 1 * Part 2 * Part 3 * Part 4

There's a very evocative description of Swinburne in WG Sebald's Rings of Saturn, in particular of his later years and unusual relationship with Theodore Watts.

ReplyDelete