"The half-brained creature to whom books are other than living things may see with the eyes of a bat and draw with the fingers of a mole his dullard's distinction between books and life: those who live the fuller life of a higher animal than he know that books are to poets as much part of that life as pictures are to painters or as music is to musicians, dead matter though they may be to the spiritually still-born children of dirt and dullness who find it possible and natural to live while dead in heart and brain."

by Gilbert Alter-Gilbert

With its driving, headlong rhythms and repetitive, trancelike drone, the imperative surge of incantatory utterances given voice by Swinburne's verse had all the strangeness of glossolalia. It rattled the guardians of tradition and shook the benumbed British mind from its tedious slumber. The startling new poetry sent shock waves shuddering through the repressed realm of Victoria Regina, not just because of its erotic content, but because of the jarring unfamiliarity of the very sound of its speech. In addition to his sexual, political, and theological provocations, Swinburne had waged what amounted to nothing less than an aural assault upon an unsuspecting England. A definitive lyric poet, Swinburne performs feats which seem to defy the physics of prosody. Tour de force is too weak a term to describe the effects he achieves routinely, almost offhandedly. With the urgency of its anapestic beat, its intricate symphonies and antiphonies alternately aggressive and lulling, its gushing rushes of adjectives strung together in alliterative syndicates and its scintillating trains of monosyllabic nouns, Swinburne's technique had, on the ear of England, the impact of a verbal avalanche.

At its most opulent, the sensorial sumptuousness of Swinburne's verse cannot be overstated; stanza after stanza of perfumed notes and chords, overlush and decadent, cascade in dizzying, indefatigable torrents of eloquence. A spasticated frenzy of compounds and concatenations all but impossibly coordinated in splurging cataracts of rhetorical excess and complex scansion; all of it building, wave after wave, into a massive onslaught of music – this was Swinburne's artistry.

To the unprepared ears of the average Victorian, Swinburne's mesmeric monotone of manic diction and emotional intensity must have seemed staggering, unimaginable – an auditory circus, a congress of wonders. To the discerning, it was literary caviar.

Like Austin Dobson, Swinburne was well at ease with the conventions of French versification. He was adept with the virelay, the sestina, and the villanelle, and is credited with having adapted the rondeau into his own invention, the English roundel. Moreover, he was an adroit practitioner of rarefied meters such as hendecasyllabics and trochaic tetrameter. Swinburne, nevertheless, was sometimes rebuked by critics for emphasizing sound over sense – a foible with which critics were to fault Dylan Thomas nearly a century later.

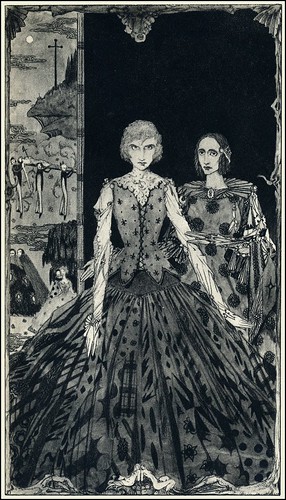

Swinburne was a lifelong Hellenist and Latinist of the highest order and a medievalist by temperament and taste, partly as a result of the principles and preferences that rubbed off on him during his affiliation with his Pre-Raphaelite brethren. He wrote verse dramas in the classical and medieval molds, featuring femmes fatales and sadomasochistic situations.

Three series of Poems and Ballads and volume on important volume of other verse; scores of scholarly treatises about fellow writers; histories; essays; historical plays and plays based on myth poured from his pen. He was a mighty workhorse who trotted out novels, hoaxes, burlesques and parodies, erotica and juvenilia, much of it still unpublished, in a continual, undifferentiated splurge.

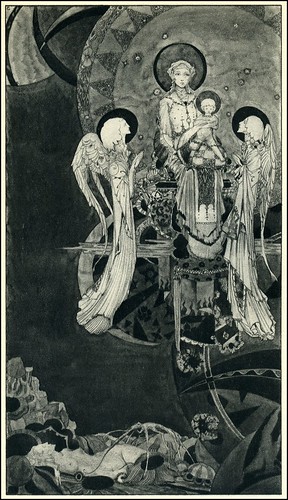

Swinburne is noted for his metaphorical depictions of desolate, inhuman landscape. Pre-Raphaelite pictorial productions tended to render nature as an enchanted fairyland of dream settings a la Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, Spenser's Faerie Queene, or Tennyson's Lady of Shallot. Though this sensibility tinged some of Swinburne's work, and he was intimately familiar with the Pre-Raphaelite painters and with the related creations of his contemporary Richard Dadd and of William Bell Scott and John William Inchbold, who were his friends, his own technique was generally Turnerian, impressionistic, and his aesthetic was that of the Sublime.

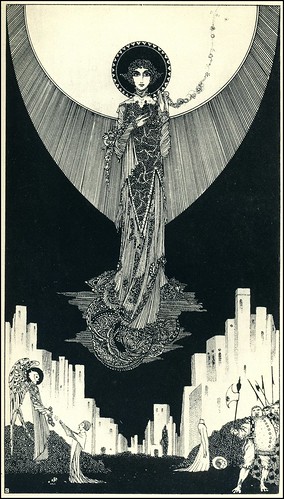

Scholar J. D. Rosenberg notes that Swinburne was "obsessed by the moment when one thing shades off into its opposite, or when contraries fuse." He was especially fixated on transitional states in nature – dawn and dusk, sea and sky; what Rosenberg terms "hermaphrodisms." Striving to express this singular sense of the inseparability of contraries, Swinburne emulated in words what his great countryman Turner had done with paint. Swinburne's various technical signatures – assonance and alliteration, synesthesia, monotony – comprised a palette prepared with incomparable virtuosity and they set him apart from all others. The "covert pathology" of his algolagnia, coupled with an exuberant morbidity and a preoccupation with exotic themes like necrophilia, sapphism, and states of sexual humiliation, combine with a truculent "theological defiance" deliberately blasphemous to the point of pastiche, to force a heretical and systematic upheaval by substituting a perverse facsimile of conventional expectations. This impulse, which permeates the preponderance of Swinburne's loftiest verse, manifests colorfully in his poisonous pantheon of cruel goddesses such as malignant Faustine and toxic Dolores. Their dolorous and baleful beauty demanding absolute adoration repaid with abasement, abjection, shame, and disgrace, emblematizes a veritable ethos of the bittersweet.

Swinburne studied painters and learned coloration from the Pre-Raphaelites and mirrored "indistinctness" and other innovations he observed in the works of Turner and Whistler. He aped Turner's diffuseness to create total impressionistic wholes displaying an "exaltation of energy over form, and infinite nuance over discrete detail." Within these parameters, Swinburne was able to give scope to his larger view of the cosmos, and of "man's fate on a cooling star." For Swinburne, that fate, according to Anthony Harrison, is "the tragedy of mankind whose pitiable part it is to strive for fulfillment through filial, erotic, and fraternal love, but, in doing so, to generate only strife and be freed from frustration and suffering only in death."

Swinburne uniquely used monotony to convey desolation. To this day, he remains unique in the application of this technique and the achievement of the resultant effect. He was equally unique in his ability to sustain a spree of highly ornate phrasings and fluid inflections perfect to the last scintilla and iota. It has been seriously speculated that the unaccustomed vigor and vivacity of Swinburne's verse and the source of its vital spark is attributable to a brain disorder. Swinburne's was a "music of enervation" in which "a sense of disorientation combined with insistent, mesmeric meters," a blurring, slurring mutedness, as if the drowsy cadences of the poem were enunciated in a dream.

Swinburne the humanist who celebrated in Hertha a Whitmanesque ideal of homo sapiens and who, as a ten-year-old Anglican ("quasi-Catholic," as he put it) had a working knowledge of biblical hermeneutics came, as an adult, to posit the presence of a God-but-not-God governing principle of the universe in which an infinitude of stars views man with cold indifference and even the supernal overlord Time Himself is susceptible to erasure. Just as his countrymen Matthew Arnold, Thomas Hardy, and James Thomson and their American cousins Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson were grappling with similar proto-existentialist notions of tragedy and pessimism, Swinburne subscribed to a "relentlessly fatalistic world view" of a sumptuous desolation void of all but Implacable Nature, tyrannical and irreducible, subject only to the supremacy of all-vanquishing Time.

The final paradox of Swinburne is his insistence on the absence of eschatological purpose or teleological scheme in the cosmos other than the rhythm of primordial forces – of oceans and tides and seasons, of the phases of nature and the predations of time. For the most part, Swinburne dispenses with cataloging the contents of Pandora's Box, unlike Baudelaire; he cleaves to a higher perspective from which he views the evils that beset mankind as mere incidentals of mortality all of which will be expunged in the ultimate onslaught – the eventual extinction of mortality and of the process of extinction itself – when, in Swinburne's own oracular words, "as a god self-slain on his own strange altar, Death lies dead."

***

Thanks for one of the most amazing posts ever - pure opium.

ReplyDeleteI'm not sure meaning always has to take precedence over sound. Of course, I say that after having been listening to Dada poetry by Hugo Ball and Kurt Schwitters, which has considerably less discernable meaning than anything by Swinburne. I'm also skeptical that Swinburne's verbal pyrotechnics were due to a brain disorder.

ReplyDeleteThose minor remarks made, I'm now feeling as though I should take a closer look at Swinburne despite his (to me) rather tedious interest in pain. It seems he has been rather neglected and relegated to curious-minor-writer-dom.

amazing series; love the clarke

ReplyDeleteA.E. Housman's essay on Swinburne, written in 1910, is one of the funniest pieces of literary criticism ever written. Perhaps it is worth quoting a couple of paragraphs:

ReplyDelete"Poetry, which in itself is simply a tone of voice, a particular way of saying things, is mainly concerned with three great provinces. First, with human affection, and those emotions which we assign to the heart: no one could say that Swinburne succeeded or excelled in this province. The next province is the world of thought; the contemplation of life and the universe: in this province Swinburne's ideas and reflections are not indeed identical with those of Mrs Hemans, but they belong to the same intellectual order as hers: unwound from their cocoon of words they are either superficial or second-hand. Last, there is the province of external nature as perceived by our senses; and on this I must dwell for a little, because there is one department of external nature which Swinburne is supposed to have made his own: the sea.

The sea, to be sure, is a large department; and that is how it succeeded in attracting Swinburne's attention; for he seldom noticed any object of external nature unless it was very large, very brilliant, or very violently coloured. But the sea as a subject of poetry is somewhat barren. Those poets who have a true eye for nature and a sure pen for describing it, spend few words on describing the sea; and their few words describe it better than Swinburne's thousands. It is historically certain that he had seen the sea, but if it were not, it could not with certainty have been inferred from his descriptions: they might have been written by a man who had never been outside Warwickshire."

Cruel, but not completely unjust... Swinburne is one of the few major English poets of whom I have been satisfied to own a selected edition (Bonamy Dobrée's well-chosen selection in the old Penguin Poets) rather than the collected works.